Contracts of employment are tools used to manage the risks of the employer-employee relationship. The employer complies with the provisions of the law while the employee seeks to enjoy the protection of the law by knowing beforehand how to mitigate possible risks.

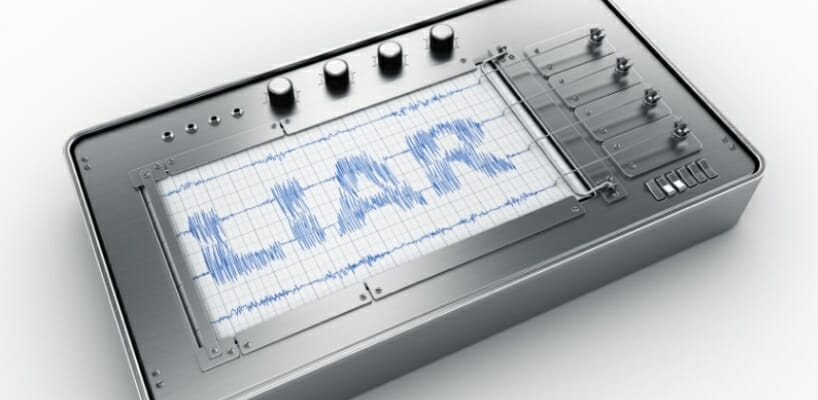

Polygraph tests are commonly used in Kenya by employers during dismissal proceedings to determine the guilt of an employee in cases of gross misconduct. In other cases, they are used to determine the suitability of an employee for promotion.

While there is no explicit law on polygraph tests in Kenya, Courts have dealt with the legality of the polygraph tests in employment dismissal proceedings. In William Kiaritha Gacheru v East African Packaging Industries Ltd [2016] eKLR, the Court was of the opinion that while there was nothing wrong with subjecting the claimant to a polygraph test, it was unfair to rely on the result of the test alone to terminate the claimant’s contracts.

The Court further held that Courts must exercise reluctance and circumspection when considering issues and procedures in employment which are purely within managerial discretion. Essentially, the Court cannot usurp this discretion and replace it with its own. Therefore, using the freedom of contract, the employer can include a term in the employment contract allowing the use of polygraph tests in specific instances during the employment relationship.

A contractual clause providing for polygraph tests on the employee allows the employer the benefits of the latest technology when investigating misconduct at the workplace. However, the polygraph clauses must be clear, and consented to at the time of signing the contract.

The employer cannot have arbitrary tests on the employees as and when they feel like doing so; such would be a violation of the employees’ rights. An employee is entitled to a fair administrative action and cannot be forced to incriminate themselves. The Court in Okiya Omtatah Okoiti v Joseph Kinyua, Public Service Commission & Attorney General (Petition 51 of 2018) declared the President’s circular illegal and unconstitutional as it violated the right to fair labour practices under Section 41 of the Constitution. The circular sought to have all public employees in senior positions subjected to fresh vetting which included the use of polygraph tests.

As per the Court’s decision in Gemalto SA v CEPPWAWU obo Louw, James & 20 others, South Africa, JA 54/14, the employee may refuse to take part in polygraph tests where the employer has not provided any good reasons for the test. The employee can also refuse to take part in a polygraph test where it violates any of their fundamental rights and freedoms, for instance, the right to fair labour practices. An employee’s refusal only becomes insubordination when the employer has a sound basis for administering the polygraph test in line with the terms of the contract.

Employers are allowed to use the polygraph tests but such a decision must obey the terms of the contract and respect the civil liberties of the employee under the Constitution (National Union of Mineworkers and Another v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation, and Arbitration and 2 Others Case No. JR 2512/2007). Furthermore, the polygraph test results alone cannot be the reason for termination of employment.

Polygraph tests are inconclusive and do not provide absolute proof of any occurrence. They merely show the physiological responses of the employee to certain questions. Thus, the admissibility of such tests even in Court, is contentious as they are not recognized under Section 48 of the Evidence Act.

The Evidence Act recognises the use of expert evidence but it does not include polygraph tests among the list of areas of expertise the Court may seek guidance. Nevertheless, expert evidence is not binding on the Court (Kimatu Mbuvi T/A Kimatu Mbuvi & Bros vs. Augustine Munyao Kioko Civil Appeal No. 203 of 2001 [2007] 1 EA 139). The Court must form its own mind (Apex Security Services Limited v Joel Atuti Nyaruri [2018] eKLR).

While polygraph tests would serve as a means to procure evidence for further investigation, it tends to reduce the employer – employee interests to a mere exchange of a shilling for labour. Polygraph tests ignore the realities of the dignity and privacy of the employee. There is need therefore for the legislators to come up with clear laws on polygraph tests in Kenya. As Neil Postman wrote in Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology, it would be a mistake to suppose that technological innovations, such as lie detector tests, have a one-sided effect. They come with their own merits and demerits.

NOTICE: This article is provided free of charge for information purposes only; it does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied on as such. No responsibility for the accuracy and/or correctness of the information and commentary as set out in the article should be held without seeking specific legal advice on the subject matter. If you have any query regarding the same, please do not hesitate to contact the following: Wamuyu Mathenge at wamuyu@wamaeallen.com.